Let's Talk Oil Prices: Rebutting Myths about the Price Collaspe

With Oil prices in free-fall, and world leaders reacting with the strange mixture of glee and terror they showed when said prices were reaching record highs in 2006-2007, there has been quite a lot of bad reporting, ill-informed analysis, and downright misunderstanding of the nature of the Oil market, and the way that supply and demand impact upon price. Anything approaching a full examination would probably stretch even my affection for long-form polemics, and as such I wanted to confine myself to responding to at least a few of the misunderstandings that drive coverage of the geopolitical aspects of the Oil market.

#1: Prices Have Collapsed!

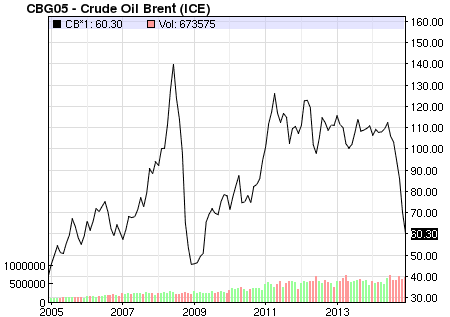

It is hard to see any coverage of the current fall in Oil prices without some reference to Oil having cost "more than $100 a barrel", or how it reached as much as $140 in 2007 before the onset of the Financial Crisis which is seen as having brought down prices by creating a "collapse in demand." As with many mainstream claims about Economics or Geopolitics, there is enough of a germ of truth within the story to prevent it from being entirely inaccurate. Oil prices did peak at those levels in 2006 and 2007, and they have fallen substantially in the last few months, reaching into the $60 range this week. But this does not mean that Oil prices have fallen by more than 50% since their peak in 2007, or that the fall has much if anything to do with "demand" in the sense that it is discussed in a Microeconomics course.

The first problem with these claims is the frame of reference. Oil prices are quoted in dollars, a sensible choice because their price is generally denominated in dollars because that makes it easy to buy and sell them. It does not, however, make it easy to track prices across time except in reference to Futures contracts within the market, because the dollar does not have a fixed value. Rather, the dollar has a variable value, one that has been very variable over the last few years. In the late 1990s, amidst the difficulties Europe experienced with the launching of the Euro, and the aftermath of currency crises in Russia and Southeast Asia, the dollar became a relative safe haven resulting in a surge that took it to nearly 150% of a Canadian dollar, with the struggling Euro being worth scarcely 70 cents.

The high deficits of George W. Bush's Administration saw a near collapse in the dollar even as the US economy posted nominally impressive growth numbers. By 2007, not only had the Euro more than doubled in value compared with America's currency, both the Canadian and Australian dollars had achieved parity and then exceeded the dollar in value.

This 35-40% fall in the value of a dollar had an obvious impact on nominal Oil prices, and at a minimum would have guaranteed a 35-40% increase in nominal Oil prices, since a dollar would be worth less. This does not mean the actual costs to consumers were different. Americans saw and felt the price increase. Europeans felt less than the nominal increase because their currencies bought more dollars. This latter dynamic evaporated in 2008, when in the space of a month, the £ lost 30% of its value against the Dollar, and the Euro around 20%. The new equilibrium lasted for the next several years with a gradual erosion in the dollar until the last month when the dollar began another surge of 6-8% or so which explains perhaps 5-7$ worth of the fall in Oil prices over the last six weeks.

Obviously this does not by itself explain the entire shift in prices, but it does explain almost half of it. That $140 barrel of oil in 2007? It would have cost about 103 of today's dollars, instead of the $60 it currently costs. This can be seen by the correlation between the following two charts, one showing the price of oil, and one comparing the value of US dollars to that of the Euro.

Oil Prices

USD/EUR

There is an almost perfect correlation through 2010, at which point the Euro crisis triggered a degree of volatility leading to a divergence, albeit one that is not great enough to prevent the current collapse from correlating almost perfectly on both. That collapse, tied to an appreciation of the dollar, is also evident in Gold prices, though in this key political factors sent gold skyrocketing even faster than the dollar beforehand.

Now as for why Gold shot up, the explanation is linked to the explanation for the other 50% of the fall in Oil prices have always been prone to conspiracy theories. After all, Oil is a fixed product; in theory everyone should know how much is produced, and therefore be able to fix prices. People definitely believed the Oil majors did so before the 1970s, most prominently the Oil producers themselves whose nationalization plans were motivated by the belief that if Western companies could control and manipulate prices so could they.

In theory this would seem to make a lot of sense. After all, if OPEC producers along with Russia extract 70%+ of the world's Oil supply, then clearly they can keep prices high by extracting less, and lower them by extracting more. Hence, a decision not to cut production, such as the one OPEC recently made, must clearly be motivated by a political motivation on the part of Saudi Arabia, whether that be to undermine the American Shale Industry, Vladimir Putin's government in Russia, Iran's Mullahs or ISIS' ability to export Oil that it has seized.

Again there is a kernel of truth to the idea that there is a correlation on some level between production of Oil and its market price. In reality however, that connection is so tenuous and indirect that few understand exactly how it works, and even OPEC Oil ministers only have a vague idea of what the impact of a production cut or increase would be on market price or when it would be felt. The reason is simple. It costs Saudi Arabia about $2 to extract a barrel of Oil, and perhaps $5-7$ in Azerbaijan, Russia or Venezuela, and that was in 2007 when the dollar was worth 30% less. Clearly, extraction costs are not the sole determinant of price.

What does determine price is the market for Oil. Oil traded on the New York Mercantile Exchange and elsewhere, and as such has more in common with commodities like Gold than it does with a stock, or an item you buy in stores. The Saudis sell Oil to companies like Exxon, which in many cases, rather than refine it themselves or ship it, sell it to third parties who then in turn put it on a tanker. That cargo made be sold hundred of times before it is purchased by a company which owns a refinery in need of crude and capable of handling that specific quality.

On one level there is a correlation between Oil supply and price, much as there is between supply of Gold and price, but only in the sense that a shift deviates from expectations. When traders purchase Gold, just as when realtors purchase land they are betting on the future price, not its present one. This is especially true when Oil is traded in the form of futures, contracts for delivery at specific times in the future. Not only is vastly more Oil traded than actually exists, but what matters for price is expectations regarding its trajectory rather than identifying where it will be along that trajectory at a given time.

Oil in the mid-2000s, it is now clear, underwent a bubble, much as Gold did following 2008, but it was a much more serious one because it attracted slightly more credible individuals, rather than mix of conspiracy mongers and those who preyed upon them who dominated Gold speculation following Barack Obama's election. The collapse in the dollar motivated those with money to invest, some in stocks, but given the internet bubble of 2000, far more in commodities or commodity-esque products such as real estate. This was aided by the fact that fixed assets maintain their value when currencies fall. As the dollar fell then, Oil and land were perceived as gaining correspondingly in value. This led investors to invest, driving their value still higher, creating a typical bubble cycle.

The Oil bubble however benefitted from a degree of legitimacy other bubbles lacked. While almost everyone acknowledged that the real estate boom of the 2000s was a bubble, albeit one they at least planned to escape before it peaked, there were semi-credible sounding individuals making logically-appealing arguments that the increase in Oil prices was permanent. They tended to focus on the idea of Peak Oil, the concept that there was a point at which world oil production would peak, and then decline until exhaustion producing ever higher prices.

The logic seemed sensible enough. Everyone knows that Oil is a finite resource, meaning that consumed Oil can no longer be utilized. As more Oil is extracted, it follows logically that less will be left, meaning at some point more will have been consumed than remains. Anyone who has taken a Microeconomics class should be able to fill in the rest. With an ever-declining supply, and an inelastic demand curve - people still will need Oil just as much for the foreseeable future, it followed that Oil prices should rise steadily and irresistibly, maybe with a few bumps along the road, but with nothing more than that. When combined with the rapid economic growth of China and India, and surging demand in those markets, the logic of the positions seemed unassailable.

And at some level it is. There is a finite amount of Oil on Earth. At some point it conceivably could be exhausted. But much as the proponents of unstoppable population growth were right in the 1970s that at some population level the Earth would become uninhabitable, but were delusional to the point of insanity about what that level would be and when it would be reached, so too were the Peak Oil alarmists who failed to grasp how much lower the actual price to extract Oil was than that on Market, how far below extraction capacity Oil producers like the Saudis were operating, and how much of the Oil in the world that is inaccessible is not so only because of cost, but also because of politics. As such, they failed to take into account that even a 50% increase in extraction costs would only bring the expense faced by the Saudis to $3 a barrel, hardly enough to bring down global civilization.

The bubble therefore sucked in far more capital than it should have, and from far more respectable people and institutions that should have known better. According to the Author Tom Bower, a subsidiary of JP Morgan bet more than $2 billion on it in 2003 after a senior executive read a book on the subject, and the Texas Billionaire T. Boone Pickens became one of its loudest advocates. These examples reveal a second factor, that many of those who bet on it early did in fact make a killing, and therefore how much of their advocacy was a scam to talk up prices and how much was genuine belief is hard to tell.

The important thing however is that this bubble did not collapse in 2009, because the partial collapse in price had other explanations that allowed it to coexist with Peak Oil, most prominently the idea that decreased demand due to lower spending power was causing the decline. As a result, Oil remained largely overpriced compared to where it should be. In fact, correcting for the Dollar's surge in value, Oil was in fact more overpriced in 2009-2010 than in 2007, as its post 2009 decline was by far less than the 30% appreciation in the dollar, meaning that most people were paying more for it in 2011 than in 2007, especially in Europe.

What's happening this fall is a delayed collapse of the bubble. With no excuses tied to the overall global economy, long-term investors are beginning to get cold feet, and it is their withdrawal that is leading to the collapse.

#3 So what about ISIS, Syria, Putin, my pet geopolitical focus?

As the above demonstrates, the Saudis, and OPEC as a whole faces much bigger problems regarding the price of Oil, and it is far from certain that a cut in supply or a price rise would reverse the trend. Because prices are set by speculation about future prices rather than current price levels, a supply contraction might cause prices to stabilize or rise by leading traders to expect higher prices in the future. But there is no guarantee that it would. Repeated supply cuts in the 1990s failed to stop Oil from dropping to $10 a barrel, and if it is market panic causing the fall, then vigorous action by OPEC might be as likely to accelerate the fall by conveying panic as it would be to reverse it. The Saudis simply don't know, and as with the Oil companies who also make a large portion of their money by trading Oil futures rather than selling actual Oil, the overriding priority for the Saudis and OPEC is a stable Oil market rather than the exact price level at a given time. The overwhelming inclination of OPEC will always to be to do nothing, and the Saudis are not exactly hurting for cash.

That is not to say that others are not. Venezuela and Iran are both in dire financial straits, and Russia's currency fell into free-fall this past month. Closer examination however presents a more varied picture. Venezuela is incapable of increasing production for political and logistic reasons, and its production has been falling consistently in any case. Russia built up massive cash reserves during the good years that in theory should have allowed the Kremlin to stabilize matters, as they did for much of this year during which a controlled devaluation shielded ordinary Russians from the full impact of sanctions. Their recent difficulties have more to do with their inability to access this money or to move their products, rather than with the prices themselves.

As for Iran and ISIS, conspiracy mongers usually chose one or the other as Saudi Arabia's target depending on which delusional view of Middle Eastern politics they adopt. What is missed is that its unclear exactly what the Saudi position in the region is at this point. There is no love lost between Saudi Arabia and Iran, but the overthrow of Assad is a pet personal project of Barack Obama and David Cameron, not something supported by the West as a whole, much less "pro-Western" governments in the region. Even discounting ISIS, the Syrian opposition is seen as stooges for Turkey and its Prime Minister, and neither the Saudis, nor the Egyptians have any interest in seeing a Turkish puppet state replace Assad. Arguably, a weak Assad is a preferable outcome to them, much as it might even be for Israel, as I have argued before. As for ISIS, their main enemy in the region is Iran and Assad, exactly the supposed targets of Saudi plotting. Observers are mistaken in assuming the Saudis must chose one side or the other. Quite simply, it is possible they are not sure of their own preferences in conflict.

That ambiguity is important, because even if containing Iran, or fighting ISIS were Saudi priorities, it is hard to imagine the Saudis putting them ahead of their own self-preservation which depends on maintaining the stability of the Oil markets, concerns that are best served currently by doing nothing and seeing how things shake out. The ambiguity and likely mixed feelings on Riyadh only detract further from the likelihood the Saudis would push for action for political reasons. And even if they were so inclined, OPEC is far from united with Qatar taking a very different position ISIS than Libya, or Venezuela.

In life, the simplest explanation is often the most accurate, and in this case it is that the Saudis are not sure what is happening in the Oil markets, not sure what is happening in Syria/Iraq, or even what they want to have happen, and have no clue what US policy is or if it will be continued by Obama's successor. As such, every interest, political and economic, mitigates in favour of inaction.